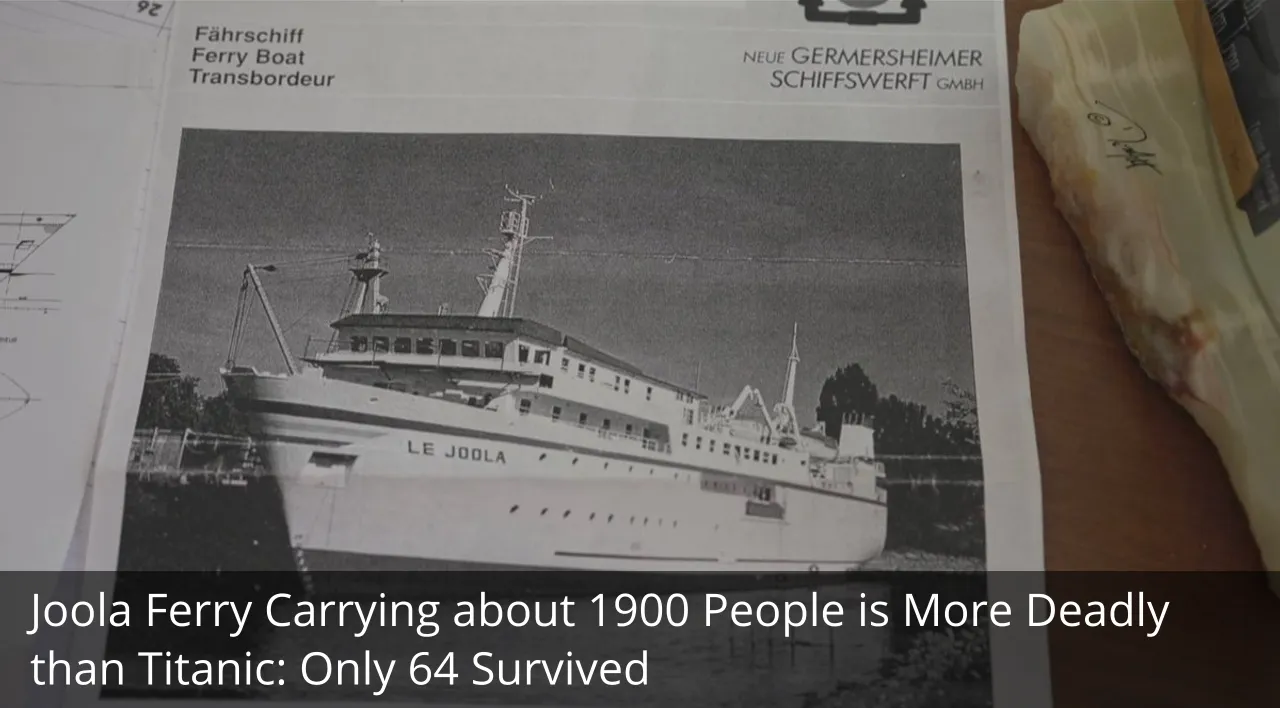

A ferry carrying approximately 1,900 people is deadlier than the Titanic. Only 64 people survived.

Senegal’s ZIGUINCHOR:

On the deck above, dozens of university students were playing cards. Passengers in the first-class cabins below watched the film “Air Force One.” On their way to a tournament, a teenage soccer team belted out songs in a crowded third-class compartment.

All were aboard the Joola ferry when it set out on a 17-hour journey from a town in southern Senegal along Africa’s west coast to the capital Dakar 20 years ago.

The celebrations abruptly came to an end as night fell. Rain began to fall on the Joola’s deck, and hundreds of passengers rushed aboard. The ferry banked to the left and then capsized, trapping the passengers.

Deadliest Shipwreck In Peacetime History

On September 26, 2002, more people died on the Joola than on the Titanic, making it the second deadliest shipwreck in peacetime history. Only 64 people survived out of over 1,900 on a ferry designed for a maximum capacity of 580. None of the 46 infants and toddlers on board survived.

However, no one was held accountable after two decades. Outside of Senegal, little is known about the Joola, and many blame lousy weather or an uncontrollable force.

Ousseynou Djiba, a mango seller who transported his goods to the market that day and cheered on the singing football team, is skeptical.

“Some say it was God’s will,” Mr. Djiba, now a teacher, said in the courtyard of his modest concrete house, where his young children were playing football. “How can it be God’s will when humans make many mistakes?”

Survivors and victims’ families, as well as multiple investigations, blame the Senegalese military for operating the ferry; government officials who ignored numerous warning signs; and the country’s top leaders, whose slow response meant that the first rescuers did not reach the Joola, which was stranded less than 90 nautical miles from Dakar, until 17 hours after the capsize. Many passengers were still alive, but rescuers lacked the necessary equipment.

The Senegalese Navy, Military, or Transport Ministries did not respond to multiple requests for comment requests.

The Survivors’ and Victims’ families Still Fighting for Justice

The survivors’ and victims’ families are still fighting to have the boat raised so they can bury their loved ones. More than 550 victims are buried in four cemeteries, but most are 59 feet deep in the Atlantic.

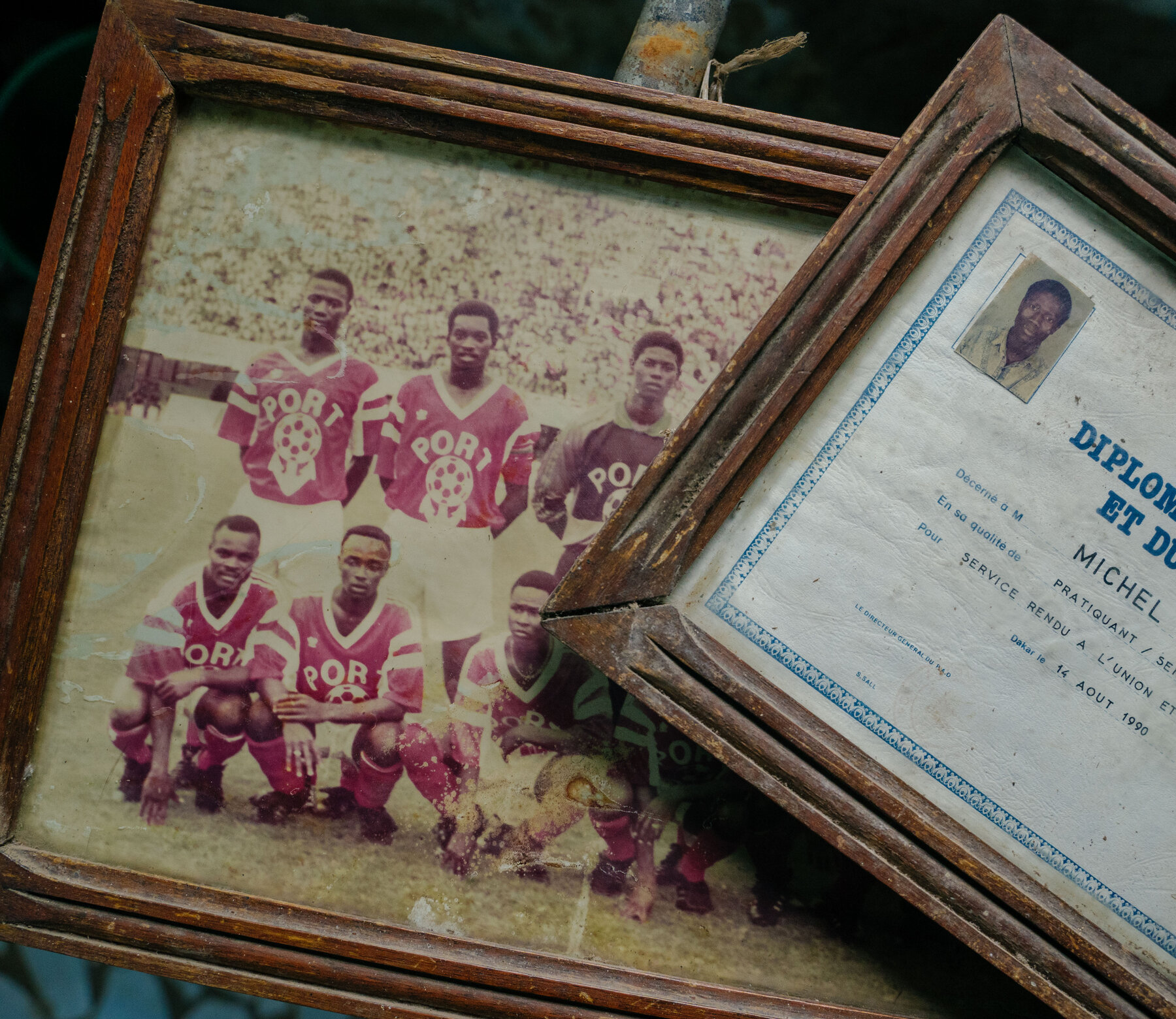

“For the last 20 years, the swell has hit these souls,” said Elie Jean Bernard Diatta, whose brother Michel was the football coach who died along with his players. “They speak to us in dreams; all they ask is that we rest in peace beneath the earth.”

In recent years, countries in Africa and Asia have witnessed a series of horrific passenger ferry accidents, including South Korea in 2014, Tanzania in 2018, and Cameroon in 2019.

However, frequent accidents on small boats navigating Senegal’s rivers and coasts have many wondering if anything has changed since the Joola disaster.

The 260-foot Joola was the answer to a windfall in Senegalese geography when she first set sail in 1990. The Gambia, a narrow strip of land stretching from Senegal’s western coast to the center, separates the southern Casamance region from central and northern Senegal.

Casamance Residents’ Cheat means of Transport to Dakar

For Casamance residents, the cheapest way to get to Dakar and the rest of the country was either by a damaged road in the east or the sea in the west.

However, the Casamance had witnessed a Separatist rebellion, and street attacks made the boat trip safer. The military took over the Joola in 1995, claiming it needed to verify passengers’ identities.

However, the ferry was frequently overcrowded.

The Joola was already tilting as she drove away from Ziguinchor, Casamance’s largest town.

Many people, including dozens of students, stayed on the upper deck to avoid the hot, crowded rooms, chatting or flirting away from the eyes of conservative parents. They returned to Dakar for the fall semester because Casamance lacked its university. Many attributed it to the central government’s discrimination against the region.

Mr. Keita: Survivor of the Disaster

Ousmane Keita, a first-year geography student who had worked on the carved wooden boats that loaded goods onto the ferry, was one of them.

“The trip was a good time to talk about October’s exams and meet up with high school friends,” said Mr. Keita, now 45 and a quiet father of two young children, as he recalled the events of that day on a recent evening, lowering his voice.

In the restaurant below, as night fell, a singer impersonating Senegal’s most famous musician, Youssou Ndour, performed.

However, clouds and strong winds were threatening the Joola. Later reports revealed that only one of the ship’s two engines was operational.

Mr. Djiba, the mango vendor, had planned to sleep on a pile of life jackets on the boat, but a guard pushed him out, forcing him to enter the restaurant. When it began to rain after 10:00 p.m., more passengers, including Mr. Keita, rushed in.

Water poured through some open portholes as the Joola banked sharply to the left. The cargo and vehicles in the garage slid from starboard to port. A large generator came loose, rocking the boat and bringing it to a halt.

People clung to whatever they could find. Some, however, fell when the boat tipped steeply.

Survivors’ Comments on The Joola Incident

The geography student, Mr. Keita, attempted to flee outside a corridor, but the slope had become too steep. Water filled the Joola. “I swam up when the boat was almost vertical,” he explained. “People were screaming and then fell silent.” The water had engulfed them.”

He was one of six survivors among the 450 students aboard the Joola that day.

Within minutes, the ferry capsized off the coast of Gambia. Its 1,400 tons and four decks turned out to be a lethal trap.

Mr. Djiba jumped out of a porthole in the restaurant and fell into the sea. He struggled to keep his grip on the capsized ferry’s hull. However, it was covered in seaweed and was extremely slippery.

The water had a strong taste of heating oil. High waves swept him away, swallowing up passenger after passenger, their screams fading into the night.

Then, from below, two hands grabbed Mr. Djiba’s feet as he lost energy in the towering waves. “I had to get rid of him underwater,” he explained. “He eventually let go.”

Also read: Will electric vehicle owners qualify for Newsom’s $400 gas rebate?

Retired Senegalese Navy Diver’s Comments on Joola

Mr. Djiba’s life rafts and life jackets were still tied to the upper deck, but he was now 39 feet down. In an interview, Ismaila Ndaw, a retired Senegalese Navy diver who oversaw safety on the Joola until days before the capsize, said the life jackets had been purposefully bound tightly. So passengers couldn’t take them with them.

“It was a shambles: whenever there was a minor incident, everyone rushed to take one,” he explained.

Mr. Djiba noticed a white figure approaching him as he drifted away from the wreck. It was one of the few loose life jackets kept in military crew members’ cabins. It was draped over a deceased passenger.

“I wanted to keep the body close to me so we could bury it,” Mr. Djiba explained. He clutched his life jacket.

According to one interviewee, about 20 passengers could climb onto the fuselage and stay there for hours. They could hear screams from below: passengers lived in air pockets that kept the boat afloat.

Authorities Learned About the Disaster From Passing Boats

However, according to subsequent investigations, no alarm was raised, and no distress call was sent to Dakar or Ziguinchor. Authorities only learned of the disaster around 7 a.m. from passing boats.

Even so, it took them hours to respond. According to a report by Senegalese investigators, the Senegalese air force did not send search and rescue aircraft until noon. Instead, fishing boats rescued the survivors after collecting the first bodies.

Mr. Ndaw, the diver’s Statement

Mr. Ndaw, the diver, was among the first to arrive. When he arrived at the ship in the afternoon and entered the restaurant, he was greeted by hundreds of corpses, some of whom were still holding hands.

He proceeded to the bow and entered the first-class cabins, which had been sealed and had not been flooded. Some passengers waved from the port windows. Mr. Ndaw, on the other hand, claimed that they were not equipped with welding torches to pierce the hull and that opening the cabin doors would have resulted in the floating boat sinking.

According to Mr. Ndaw, none of the passengers he saw alive in the cabins were rescued.

He stated that he received the order to recover the bodies, which he and his colleagues did over the next ten days. He, the other response team members, and the survivors continue to suffer from depression and insomnia. Mr. Ndaw scratches his nostrils obsessively, a tic he claims he developed “because of the smell.”

The Errors That Led To The Tragedy: Documented

The errors that led to the tragedy are listed below, now well documented: the Joola lacked a sailing license; its crew never contacted a meteorologist before setting out, and the captain failed to ensure the ferry was balanced regularly.

A year later, a Senegalese prosecutor closed the investigation into the disaster, ruling that only the captain, who died, was to blame. In France, a judicial inquiry that resulted in 18 victims was dropped in 2014.

Instead, authorities offered $15,000 in compensation to each survivor or victim’s family on the condition that no one sue the government.

Also read: Are California’s High Gas Prices the Fault of Governor Gavin Newsom?

20 Years Later University Established in Ziguinchor

Twenty years later, Ziguinchor, which lost nearly 1,000 residents on the Joola, has partially recovered. In 2007, a university was established to provide local students with an alternative to the one in Dakar. The Joola was replaced by a new ferry.

Mr. Keita attempted to resume his geography studies after the disaster but was hospitalized for a month. He changed his mind about the sixth anniversary after a government minister said, as Mr. Keita recalled, that it was time “to move on with this anniversary cause.”

Mr. Keita was deployed and fell into the nearby Casamance River, where he was rescued and hospitalized again. He never traveled by sea or river again as a mobile phone shop owner.

“I’m not strong enough to handle the boat,” he admitted.

The Government: Museum To Commemorate The Tragedy

A museum to commemorate the tragedy is still under construction in Ziguinchor. Divers recently collected wreckage objects for display. Mr. Ndaw stated that the skeletons were still present in the cabins and on the boat.