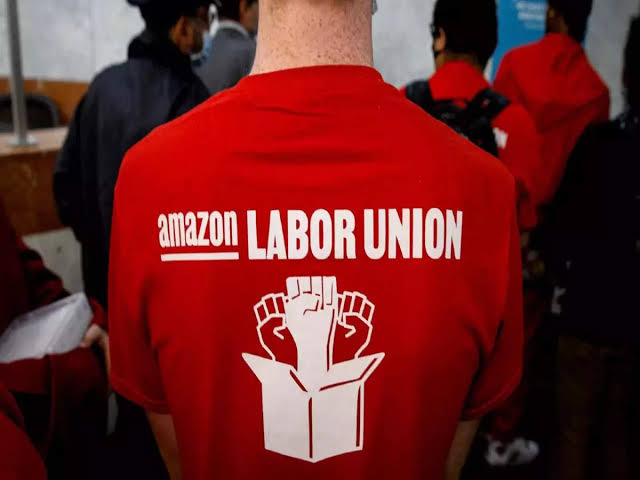

Following a surprising victory at Amazon by a little-known union, organized labor has begun to see itself in need for new developent and changes.

“It’s sending a wake-up call to the rest of the labor movement,” said Mark Dimondstein, the American Postal Workers Union president. “We have to be homegrown — we have to be driven by workers — to give ourselves the best chance.”

According to New York Times, Protests have been organized by tech workers at Google and Netflix over issues such as sexual harassment and prejudice against transgenders. The Starbucks unionization campaign, where workers have voted for unionization in 10 corporate-owned stores and placed ballots in roughly 150 more over the past six months, has largely been conducted via email, text and Zoom, while Workers United, an affiliate of the SEIU, oversees it.

“I can give my opinions — experience means something, but living it means more,” said Richard Bensinger, an organizer for Workers United, pointing to the difference between featuring as an outsider and as an employee of a company.

In her book “No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age,” the organizer and scholar Jane McAlevey wrote skeptically of two common approaches of established unions. One is “advocacy,” in which union officials try to hammer out deals with corporate executives or political power brokers to allow workers to unionize, but with little input from workers.

Ms. McAlevey also questioned an approach she called “mobilization,” in which the union takes on an employer primarily through the efforts of a professional staff, consultants and a cadre of activists rather than a large group of rank-and-file workers. “The staffers see themselves, not ordinary people, as the key agents of change,” she wrote.

Critics typically acknowledge that the campaigns helped galvanize support for higher wages even if they fell short of unionizing workers.

Defenders say the goal is to have an impact on a company- or industrywide scale rather than a few individual stores. They point to certain developments, like a pending California bill that would regulate fast-food wages and working conditions, as signs of progress.

In other cases, workers themselves have perceived the limitations of established unions and the advantages of going it alone. Joseph Fink, who works at an Amazon Fresh grocery store in Seattle with roughly 150 employees, said the workers there had reached out to a few unions when seeking to organize in the summer but decided that the unions’ focus on winning recognition through National Labor Relations Board elections would delay resolution of their complaints, which included sexual harassment and health and safety threats.

In recent years, a variety of groups have sought to make it easier for workers to organize independently.

The problem for independent organizing efforts is that their momentum can be hard to sustain, even with such cutting-edge tools, or after securing a win through a strike or an election.

“The organizing never stops,” said Kate Bronfenbrenner, director of labor education research at Cornell University.

“You can’t sit back. For a normal first contract campaign, it averages three years. If Amazon contests this in court, this is going to take a lot longer.”

For some worker-led unions, some challenges may point to the need for a hybrid approach in which they retain control of their organizations but seek guidance and resources from more established unions.

Staten Island Amazon workers received free legal assistance from union employees as well as office space, and the Communications Workers of America provided them with a messaging platform that allowed them to send group texts to coworkers. In Starbucks, Workers United has paid for extensive legal work, including contesting the election petitions of the company.

The question is whether traditional unions will be able to resist the temptation to seize control from workers whose energy fueled these demands, even as they increase their contribution to these efforts, including opposition research and other public relations strategies. Postal workers union leader Dimondstein advised his fellow union leaders to play a similar long game and stand down in favor of the Amazon campaign.

“We need to make sure this doesn’t break down into jurisdictional fights — who’s getting these types of workers, these members,” he stated.

When questioned if he thought existing unions would be able to resist that temptation, Mr. Dimondstein said. “Well, I don’t know how confident I am,” he said. “I know it’s necessary.”